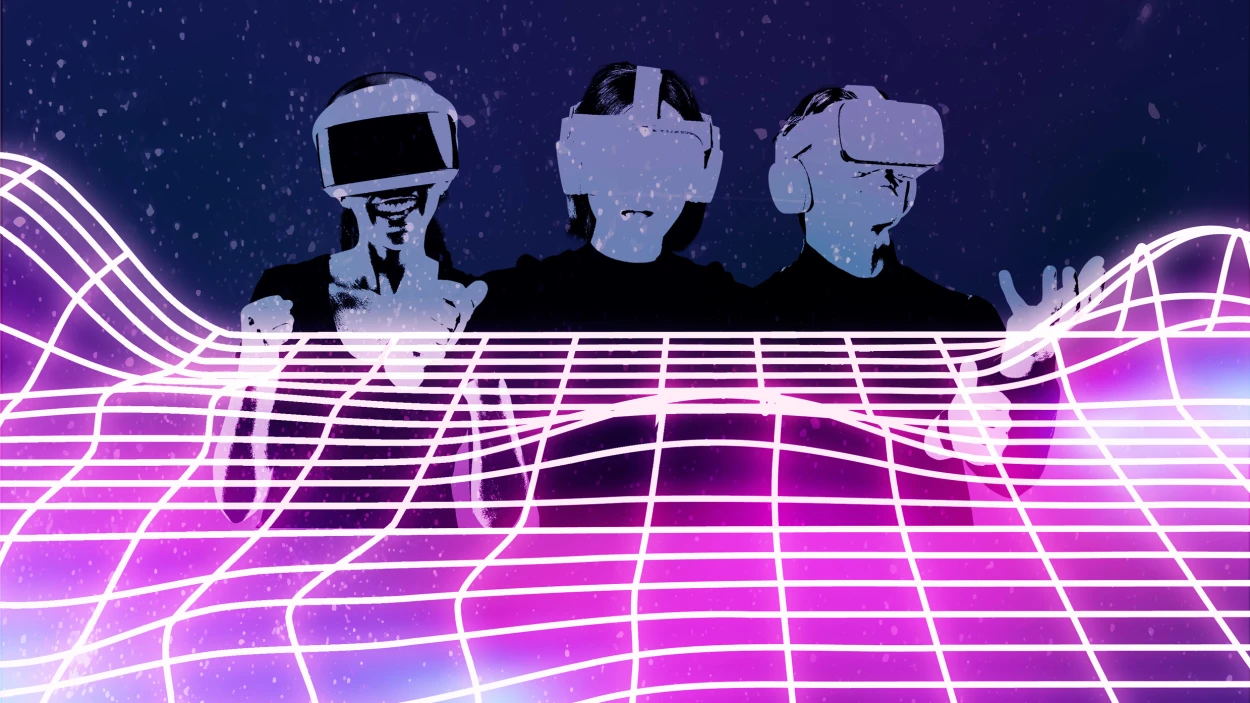

How AI Can Accelerate And Democratize Metaverse Development

Metaverse development is undeniably expensive. Like video games, these environments are immersive and highly visual products that require a multidisciplinary development team of programmers, artists, and writers. Compounding matters, they have ongoing operational costs, as the experience needs to be staffed, maintained, and expanded throughout its lifetime. And I haven’t even mentioned the price of deployment, with virtual real estate and streaming often commanding steep prices.

For smaller companies, entering the metaverse is simply beyond reach. If we assume initial development costs between $500,000 and $2 million, and development timelines ranging from one to two years, it becomes apparent that an entire class of business is completely priced out of this sector. While AI isn’t a silver bullet for this problem, it can help reduce up-front and ongoing costs, making the metaverse more accessible.

Likewise, there are several apparent opportunities. The AI agents described earlier can assume the role of human employees, or augment a small team staffing a metaverse experience. They’ll help companies transcend budgetary limitations, allowing them to provide a white-glove experience around the clock, thus reaching customers and users in other regions and time zones.

Labor costs represent a significant portion of the ongoing costs of a metaverse product. If a company wants to staff its experience 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it will likely need at least five employees. Assuming each earns a salary of $60,000, we end up with a labor cost of $300,000 per annum.

While it might be impractical or undesirable to have a fully automated metaverse experience, it’s not inconceivable that a brand would choose to rely on AI during the experience’s quietest hours, allowing it to save on labor costs without also having to close its doors to visitors. There’s less likelihood of disruption caused by sickness or planned vacations, and the brand becomes more resilient to hiring difficulties—an ongoing problem in most industrialized countries.

AI will also play an essential role in the narrative construction of the metaverse. Generative AI products like ChatGPT have shown an uncanny ability to craft text to a variety of styles and about a variety of themes. For metaverse developers, its potential applications are vast, from responding appropriately to questions from visitors to crafting the language used in sprites, documentation, and other scripted elements of the experience.

Again, this won’t necessarily come at the expense of human employment. Someone will have to craft the prompts sent to the generative AI system and check the results for “correctness,” both factual and tonal. Additionally, any system used to respond to ad-hoc queries from users will need to be tested vigorously and refined before deployment. But even with those new tasks, it’s readily apparent how AI will help metaverse developers reduce costs and development time.

How The Metaverse Can Influence AI Development And Policy

Artificial beings are a common science fiction trope, exemplified by the likes of Star Trek’s Lieutenant Commander Data and Isaac Asimov’s Robbie. And they remain—at least for now—limited to the world of television, film, and literature. The technology required (particularly general AI, which remains purely theoretical) simply doesn’t exist.

Yet where these works of fiction agree is the potential societal and economic benefits of an automated human that can act like—but, crucially, isn’t—a human, and the need to create a series of rules and guidelines so that the technology can be used safely. Data famously couldn’t kill, and Asimov created the Three Laws of Robotics, which continue to influence AI policy and ethics.

The most serious works of science fiction often try to make earnest predictions about the future, whether through cautionary tales or utopian visions, and in doing so influence the present. But in reality, we can often really measure the impact of new technology only in hindsight. Once promising innovations—like leaded gasoline or Freon gas—have eventually come to be recognized as societal and environmental disasters.

In a recent article, Tom Wheeler of the Brookings Institution argued the need for strong rules for AI-powered metaverse agents to limit or, at the very least, mitigate any potential harm. Wheeler makes some salient (and perhaps even prescient) points, acknowledging the nuance between a simple video game and a metaverse, which by definition is a virtual world where people can interact, transact, and work.

The metaverse, he acknowledges, is really an AI-powered metaverse—where many of the characters and figures users encounter will be sophisticated machines that leverage the latest advances in generative AI. He recognizes that it will have a cross-demographic appeal, and there will be an urgent need from regulators and tech giants alike to ensure user safety, particularly when protecting individuals from harassment and abuse, and businesses from fraud and theft.

Wheeler correctly notes that the metaverse’s prominence (both societal and economic) means the old adage of “move fast and break things” no longer makes sense, and is likely very dangerous. Underlying his paper is a tone of urgency, which I share, but also pessimism, which I don’t.

Remember: The metaverse is designed to complement and augment the physical world. As metaverse adoption accelerates, it’s inevitable that many of the most exciting and promising advances in AI technology will be pioneered within virtual worlds before reaching other industries and the wider society.

As a lower (but not necessarily low) stakes environment, the metaverse is an ideal proving ground for many AI technologies, allowing developers to identify and remedy potential issues before widespread deployment. In that respect, metaverse developers and AI developers will eventually find themselves in a symbiotic relationship, each benefiting from the other’s success.

But that can happen only under the right regulatory environment. It’s incumbent upon legislators and developers to work collaboratively to find the right balance that allows innovation to progress unhindered while protecting users from potential harm.

New Horizons

Conceptually, while still in its infancy, the metaverse is a promising technology that’s set to radically reshape not only the internet but also our daily lives. And yet there’s still so much uncertainty, not just about timelines but also about how the mechanisms of this new digital ecosystem will work in practice.

We don’t know who the biggest players will be, whether any open standards will emerge (thus allowing for interoperability among platforms), and what platform will ultimately reign supreme. Or even if there will be a dominant platform.

Still, we can say with a high degree of certainty that AI will play an outsize role in the development of the metaverse, and vice versa. Artificial intelligence will be the rising tide that buoys all ships, both large (and cash-rich) conglomerates and plucky startups working from a shoestring budget.

For the largest brands and developers, AI will allow for the creation of ambitious, always-on, large-scale metaverse experiences. The same will be true for young startups, but they’ll also benefit from reduced development costs and a shorter time to market.

For many companies, AI will turn the metaverse from an ambition to something firmly within the realms of possibility. It’ll be a democratizing force, just like the Commodore 64 was for the home computer.

It’s also worth emphasizing that what I’ve described isn’t theoretical; it’s already eminently possible. Brands can already start building their own AI-powered agents by creating a custom system around an existing large language model like OpenAI’s GPT-4, or through an off-the-shelf solution like UneeQ’s Digital Humans. They can start using ChatGPT to craft the scripted parts of their experience, in turn allowing for richer and more expansive storytelling.

These tools are capable, and they’ll only get better over time. Just ask them.

Josh Rush is the CEO of , a virtual events and metaverse development platform.